Quarries

QUARRIES

Artist’s Statement

“The concept of the landscape as architecture has become, for me, an act of imagination. I remember looking at buildings made of stone, and thinking, there has to be an interesting landscape somewhere out there because these stones had to have been taken out of the quarry one block at a time. I had never seen a dimensional quarry, but I envisioned an inverted cubed architecture on the side of a hill. I went in search of it, and when I had it on my ground glass, I knew that I had arrived. I had found an organic architecture created by our pursuit of raw materials. Open-pit mines, funneling down, were to me like inverted pyramids. Photographing quarries was a deliberate act of going out to try to find something in the world that would match the kinds of forms in my imagination.

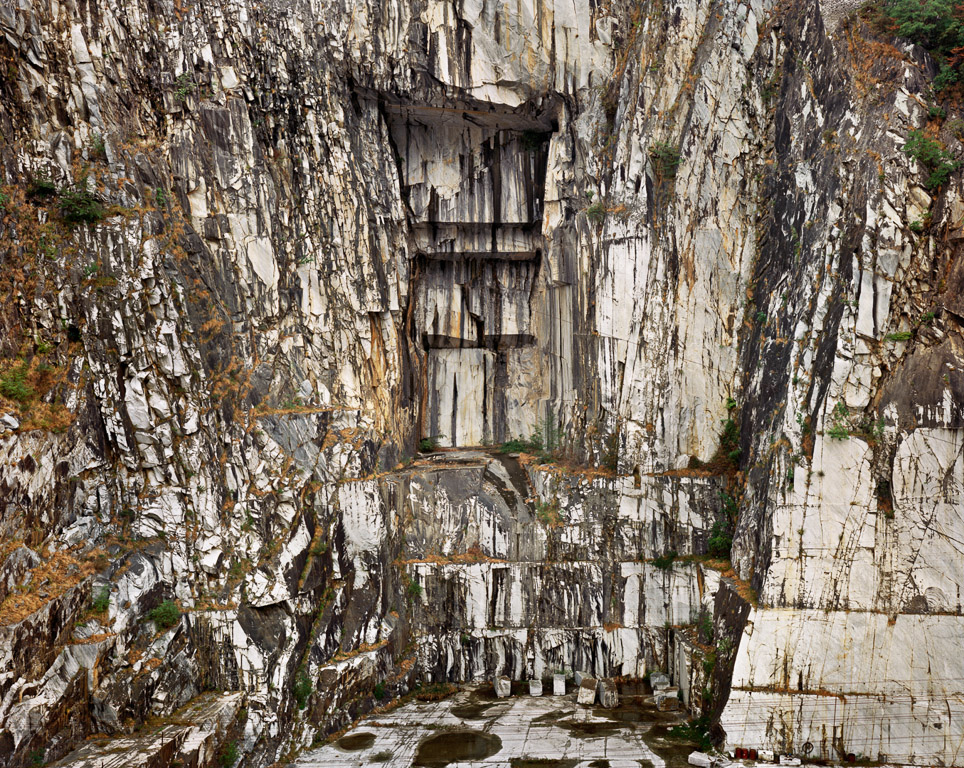

I was excited by the striking patinas on the walls of the abandoned quarries. The surface of the rock-face would simultaneously reveal the process of its own creation, as well as display the techniques of the quarrymen. I likened the tenacious trees and pools of water to nature's sentinels awaiting the eventual retreat of man and machine - to begin the slow process of reclamation.

Often my approach, the compression of space through light and optics, also yields an ambiguity of scale. I think that people are always trying to put a human scale on things. We need to put our human perspective into these images, and our presence is dwarfed by the spaces we’ve created. It's an interesting metaphor for how technology seems larger than life, larger than our own lives.” – Edward Burtynsky

VERMONT:

Edward Burtynsky got to Barre for the first time in 1991 as a result of a photographic quest for quarries in Northern Ontario. When he expressed his disappointment with the small scale of operations in Temagami, a quarryman there described a series of spectacular quarries he’d seen in Vermont. He packed his gear and began the long drive southeast to Barre. It was a trip that launched his career.

For the artist, it suggested inverted architecture: an idea about quarries that he had long dreamed of, but in the eyes of the quarryman it was an evolutionary history of extraction technology. In all, Edward Burtynsky made a half dozen Vermont trips to photograph what are thought to be the deepest quarries in the world.

CARRARA:

Like many of us, Burtynsky went to Carrara dreaming of Michelangelo. But after a long flight and an even longer mountain drive he found the road to the master’s favourite quarry chained off a dozen kilometers from the source. His view of that historic marble mountain from across the adjacent valley records the closest he ever got. Yet frustrated plans can yield unexpected opportunities. A nearby quarry suggested as an alternative proved to be a picture-maker’s windfall. The creamy, flawless marble made a perfect white ground for the machines, cables and tools of the quarryman’s trade. In the diptych Carrara Marble Quarries # 24 & 25, the chainsaw-like block cutters slowly make their way along short track sections on the quarry floor. It’s as if they’re cutting cake. Today there are over one hundred active quarries around Carrara. They employ a thousand workers who extract a million tons of marble each year.

MAKRANA:

The marble quarries of Makrana have supplied stone for some of the most storied and beautiful structures in all of human history―the Jain temples of Mount Abu and Ranakur and that shimmering monument to lost love, Agra’s Taj Mahal. However, for many Indians the Makrana quarries are the Pits of Death. At least half a dozen workers die in the quarries every month and there have been more than 500 serious accidents in the past half decade. Additionally, there is an enormous and poorly documented host of occupational illnesses and injuries—silicosis, deafness and loss of limbs. In 2005 alone, more than fifty local mines collapsed. This beauty has an enormous capital cost.

The requisite dynamite blasts are regularly set off with no advance warning to workers in the pits. A worker here must be fearless. There is always an adjacent mosque for prayers by the Muslim workforce. When Burtynsky was photographing the region’s largest quarry, an enormous block being hoisted by cable slipped free and crashed down the bedding slope, firing rock chips at the photographer and his crew. For the quarry owners, workers who survive to age thirty-five are old and obsolete.

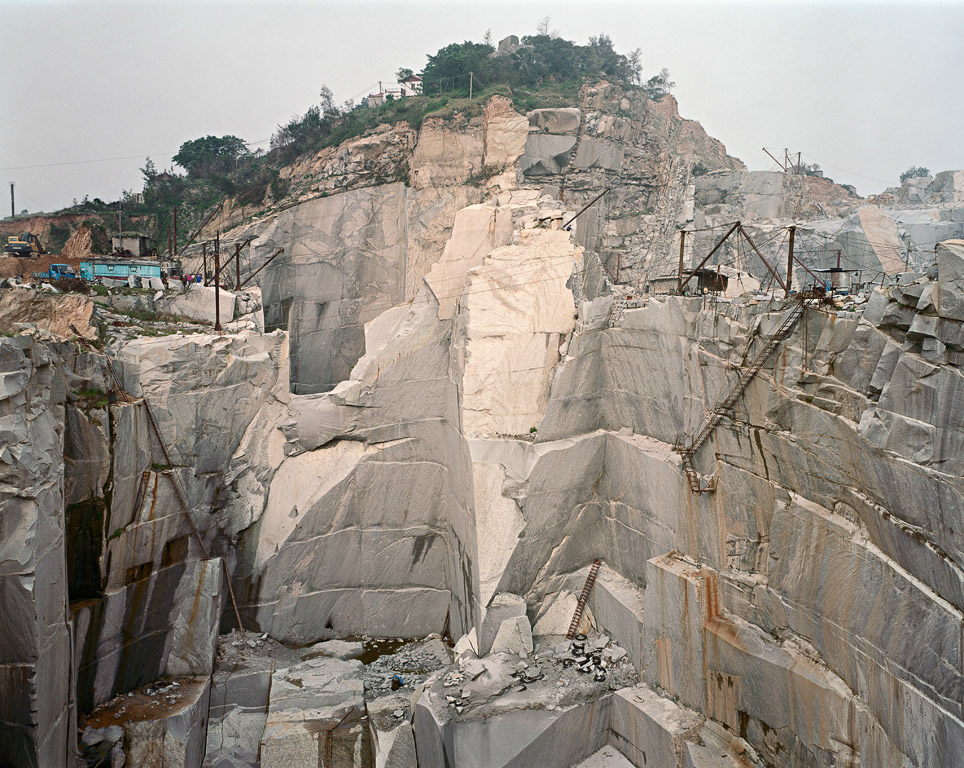

XIAMEN:

Since Deng Xiaoping began opening China’s economy to the world in 1978, economic growth in coastal provinces like Fujian has been phenomenal. The high-grade granites near Xiamen have led to the development of more than a hundred local quarries and thousands of stone product workshops employing nearly a million people. The skilled stone carvers seen working in image China Quarries #8 will make you a life-size likeness of Michelangelo’s David in granite for under a thousand dollars. Send them a photograph of yourself and they’ll do one of you for the same price.

The story of this trade in China is very similar to that of its main rival, India. Their vigorous assault on the land reminds us of our own experience in the West more than a century before.

IBERIA:

The quarries of southeastern Portugal are often extremely deep. The operation in Iberia Quarries #9 has reached a depth of more than 450 feet. These pits, with their precipitous walls and profound depths, dictated extreme solutions to the photographer’s fundamental problem of where to stand. The photograph of the Cochico company’s quarry at Pardais (Iberia Quarries #8) was made using one of the orange-painted elevator platforms cantilevered from the lower right wall of the pit. Here, nearly a quarter century after his initial encounter with the quartz mine photograph at Canada’s National Gallery, Burtynsky had finally found a site that allowed him to make homage to the inspiration provided by August Sander. For Burtynsky, these Portuguese quarries represented the culmination and conclusion of a fifteen-year search for his dream image of an architecture turned inside out and upside down. Turn the image Iberia Quarries #3 upside down and there it finally is – the inverted ziggurat that he had so long imagined. His quarry work was complete.