African Studies

ARTIST STATEMENT

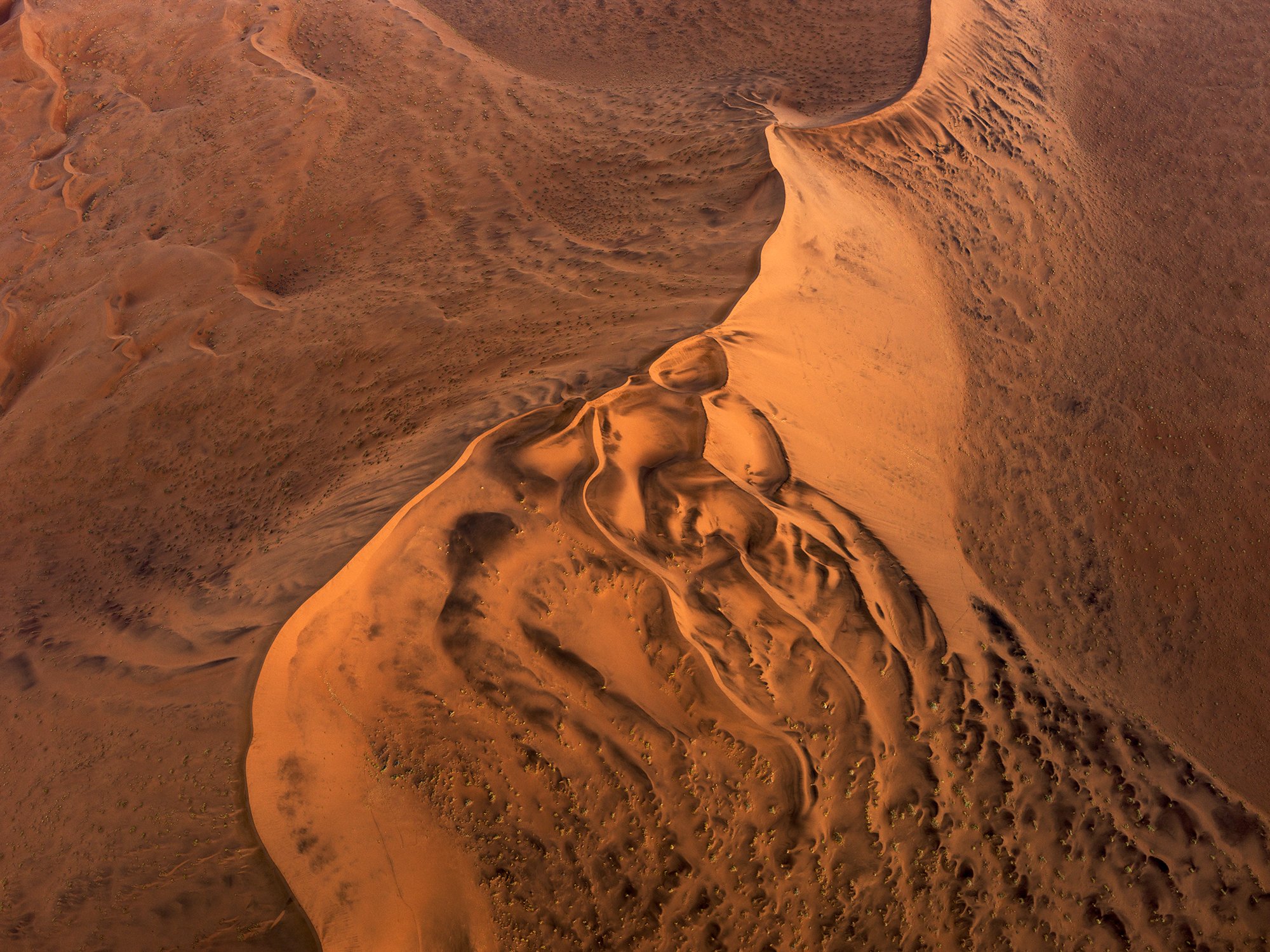

The 54 countries of Africa are divided physically through its center by the Sahara Desert and encompass a broad spectrum of governments and economies. This project, focussing on sub-Saharan Africa, has taken me to Kenya, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Senegal, South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Madagascar and Tanzania but the complex and diverse nature of this vast continent cannot be defined neatly in a book of images. Over the past seven years, during the course of my observations across sub-Saharan Africa, the title African Studies came to mind, as it most appropriately reflects this experience.

My interest in Africa owes its genesis to an earlier body of work that I produced about China back in 2004. For that project, and while researching several topics including the Three Gorges Dam, urban renewal, and recycling, I learned how the new Chinese factories were being created. At the time, heavy machinery was literally being unbolted from concrete floors in Europe and North America, then shipped and refastened to the floors of gigantic facilities in China. This represented a paradigm shift of industry, and it seemed obvious that China was rapidly becoming a leading manufacturer for the world. I realized even then that the African continent was poised to become the next, perhaps even the last, territory for major industrial expansion.

Two decades later, globalism has indeed rapidly evolved. In 2016, China’s general assembly presented a new vision for their country, announcing boldly that they wanted to create tens of millions of offshore manufacturing jobs over the next decade in order to move China towards becoming a service economy. The governing bodies considered several key issues, among them: concern about the degree of air and water pollution that domestic industrial activity was inflicting on the homeland, and that demand for wage increases was consequently increasing production costs to substantially higher levels than could be afforded in countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia and in numerous countries within Africa. Another consideration, which was tied to the now defunct one-child policy; there was also an over-abundant population of young Chinese men and finding work abroad for them would help deal with this imbalance.

[…]

Across Africa, as with most other places in the developed and developing world, far too great a price is paid by its fauna, forests and Indigenous peoples. With this project I hope to continue raising awareness about the cost of growing our civilization without the necessary consideration for sustainable industrial practices, and the dire need for implementing globally organized governmental initiatives, with binding international legislations, in order to protect present and future generations from what stands to be forever lost.

Homo sapiens began migrating out of Africa as early as 200,000 years ago. Fast-forward to the 21st century and we’ve come full circle, returning to one of the last places on Earth to be swept into the unrelenting machinations of the human industrial complex. With our ever-increasing population and requisite appetite for unlimited economic and technological expansion, the African continent, boasting a tremendous wealth of unexploited resources, is a fragile, final frontier — resting squarely in the crosshairs of progress.

— Edward Burtynsky

Xylella Studies

Xylella fastidiosa is a vector-transmitted bacterial plant pathogen associated with serious diseases in a wide range of plants. It causes Pierce’s disease in grapevine, which is a major problem for wine producers in the United States and South America. X. fastidiosa was detected on olive trees in Puglia, southern Italy, in October 2013, the first time the bacterium was reported in the European Union. Since then it has also been reported as present in France, Spain and Portugal and Brazil. By 2015, the disease had infected up to a million olive trees in Apulia. Numerous species of xylem sap-sucking insects are known to be vectors of the bacterium. X. fastidiosa also has a broad range of host plants, including many common cultivated and wild plants.

In 2021, Burtynsky was commissioned by Fondazione Sylva (Lecce district) to document the deteriorating state of the olive groves in Apulia.

Natural Order

ARTIST STATEMENT

During this time spent in isolation and while reflecting on this historic moment and the gravity of these events, I have taken the opportunity to once again turn my lens to the natural landscape as subject matter. The result is this new series, made during the time of year when the cycle of renewal exerts itself on the Earth. From the frigid sleep of winter to the fecund urgency of spring, these images are an affirmation of the complexity, wonder and resilience of the natural order in all things. I find myself gazing into an infinity of apparent chaos, but through that selective contemplation, an order emerges — an enduring order that remains intact regardless of our own human fate. These images are all from a place called Grey County, Ontario. They are also from a place in my mind that aspires to wrest order out of chaos and to act as a salve in these uncertain times.

– Edward Burtynsky

Anthropocene

ARTIST STATEMENT

“My earliest understanding of deep time and our relationship to the geological history of the planet came from my passion for being in nature.

[…]

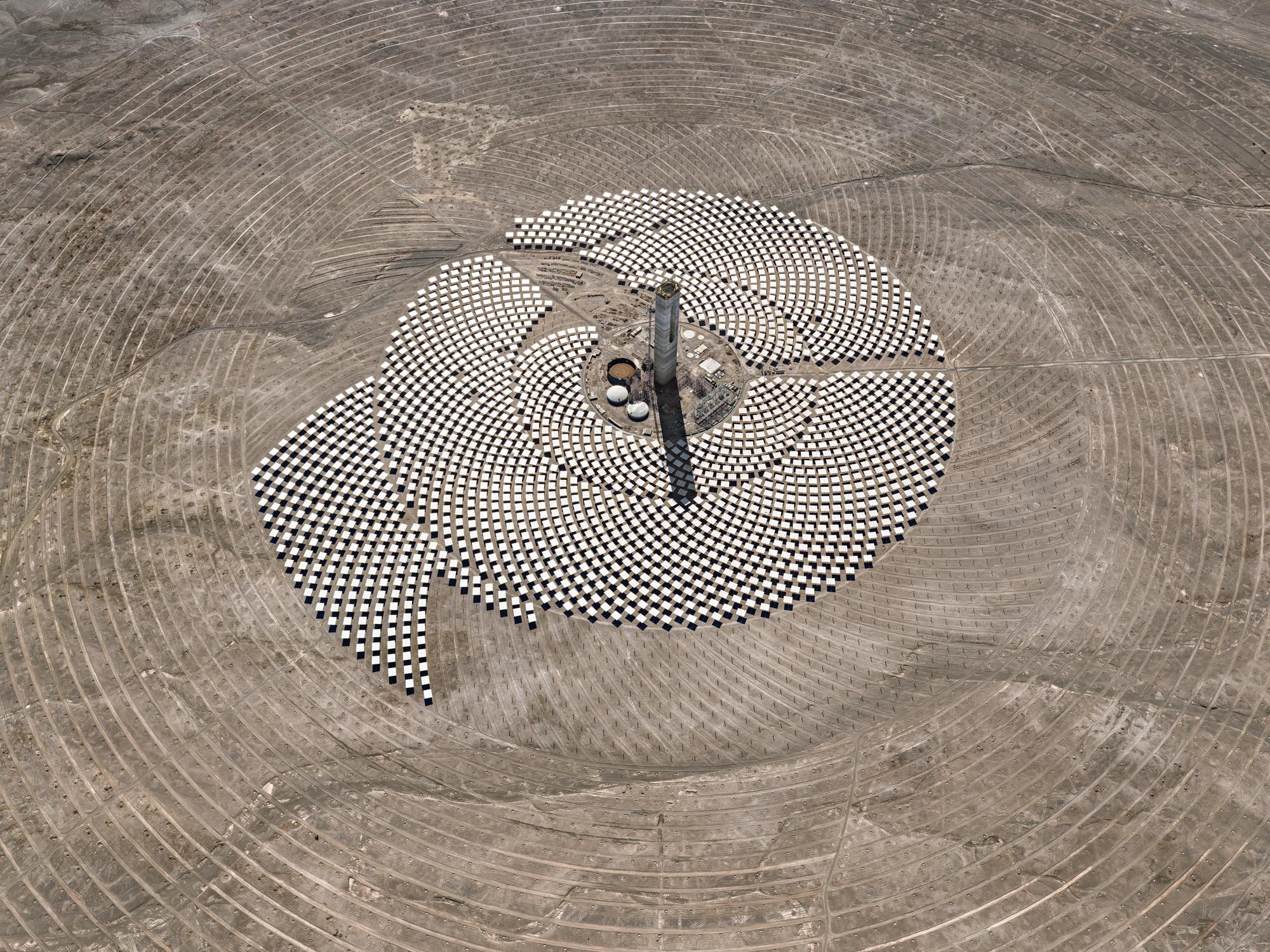

Our planet has borne witness to five great extinction events, and these have been prompted by a variety of causes: a colossal meteor impact, massive volcanic eruptions, and oceanic cyanobacteria activity that generated a deadly toxicity in the atmosphere. These were the naturally occurring phenomena governing life’s ebb and flow. Now it is becoming clear that humankind, with its population explosion, industry, and technology, has in a very short period of time also become an agent of immense global change. Arguably, we are on the cusp of becoming (if we are not already) the perpetrators of a sixth major extinction event. Our planetary system is affected by a magnitude of force as powerful as any naturally occurring global catastrophe, but one caused solely by the activity of a single species: us.

[…]

I have come to think of my preoccupation with the Anthropocene — the indelible marks left by humankind on the geological face of our planet — as a conceptual extension of my first and most fundamental interests as a photographer. I have always been concerned to show how we affect the Earth in a big way. To this end, I seek out and photograph large-scale systems that leave lasting marks.

[…]

As a collaborative group, Jennifer, Nick and I believe that an experiential, immersive engagement with our work can shift the consciousness of those who engage with it, helping to nurture a growing environmental debate. We hope to bring our audience to an awareness of the normally unseen result of civilization’s cumulative impact upon the planet. This is what propels us to continue making the work. We feel that by describing the problem vividly, by being revelatory and not accusatory, we can help spur a broader conversation about viable solutions. We hope that, through our contribution, today’s generation will be inspired to carry the momentum of this discussion forward, so that succeeding generations may continue to experience the wonder and magic of what life, and living on Earth, has to offer.”

— Edward Burtynsky

* Extract from Burtynsky’s essay, “Life in the Anthropocene” in the Anthropocene book.

Anthropocene is a multidisciplinary body of work by Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, which includes a photobook, a major travelling museum exhibition, a feature-length documentary film, and an interactive educational website. The project’s starting point is the research of the Anthropocene Working Group, an international body of scientists who argue that the Holocene epoch ended around 1950, and that we have officially entered the Anthropocene in recognition of profound and lasting human changes to the Earth’s system.

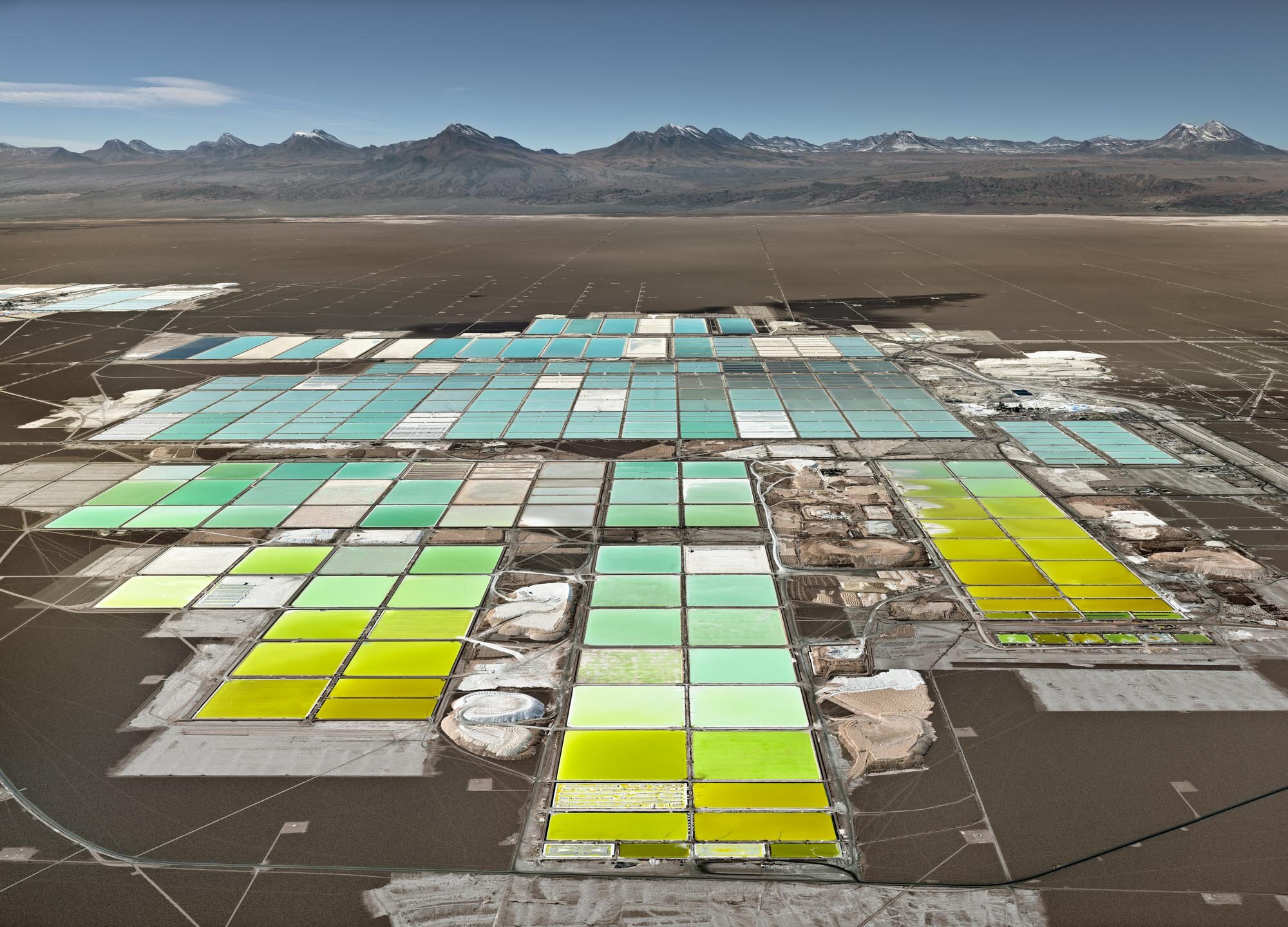

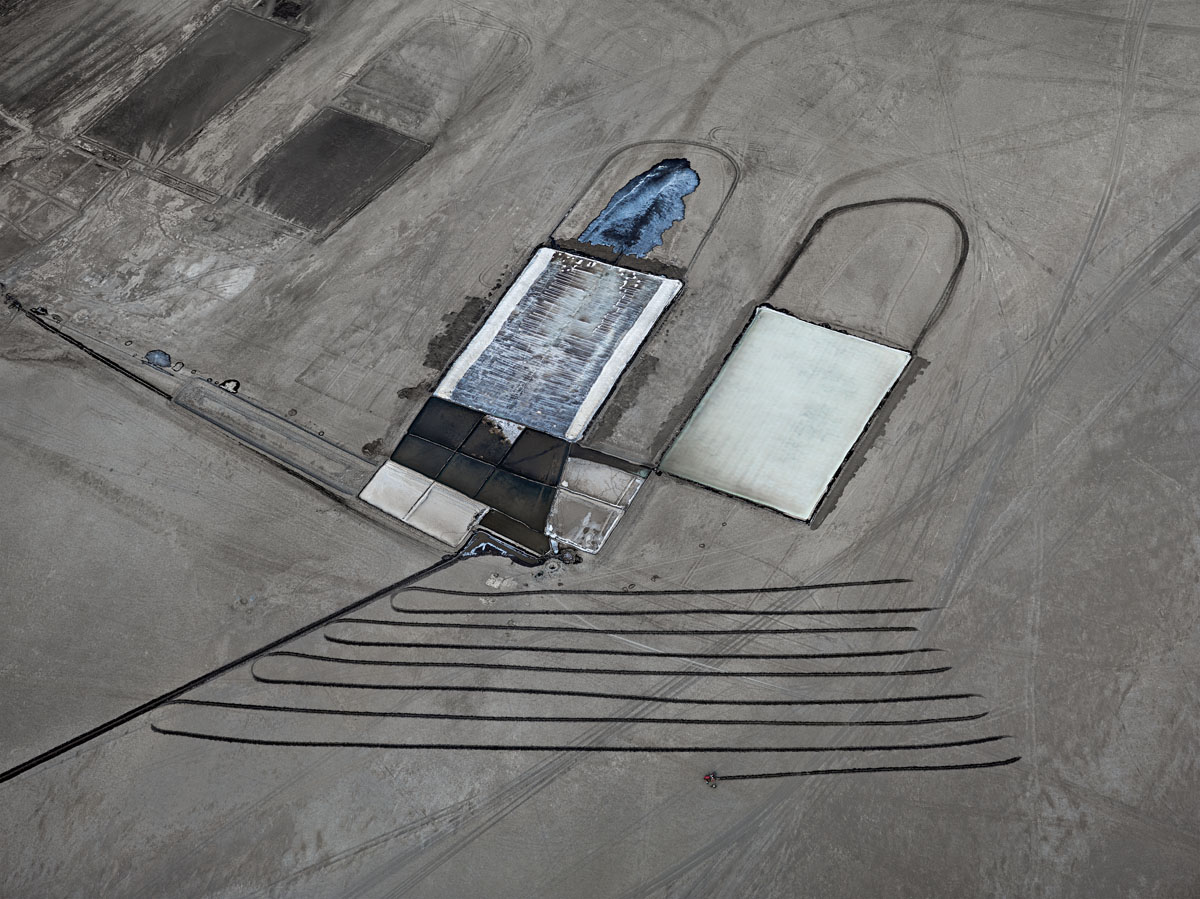

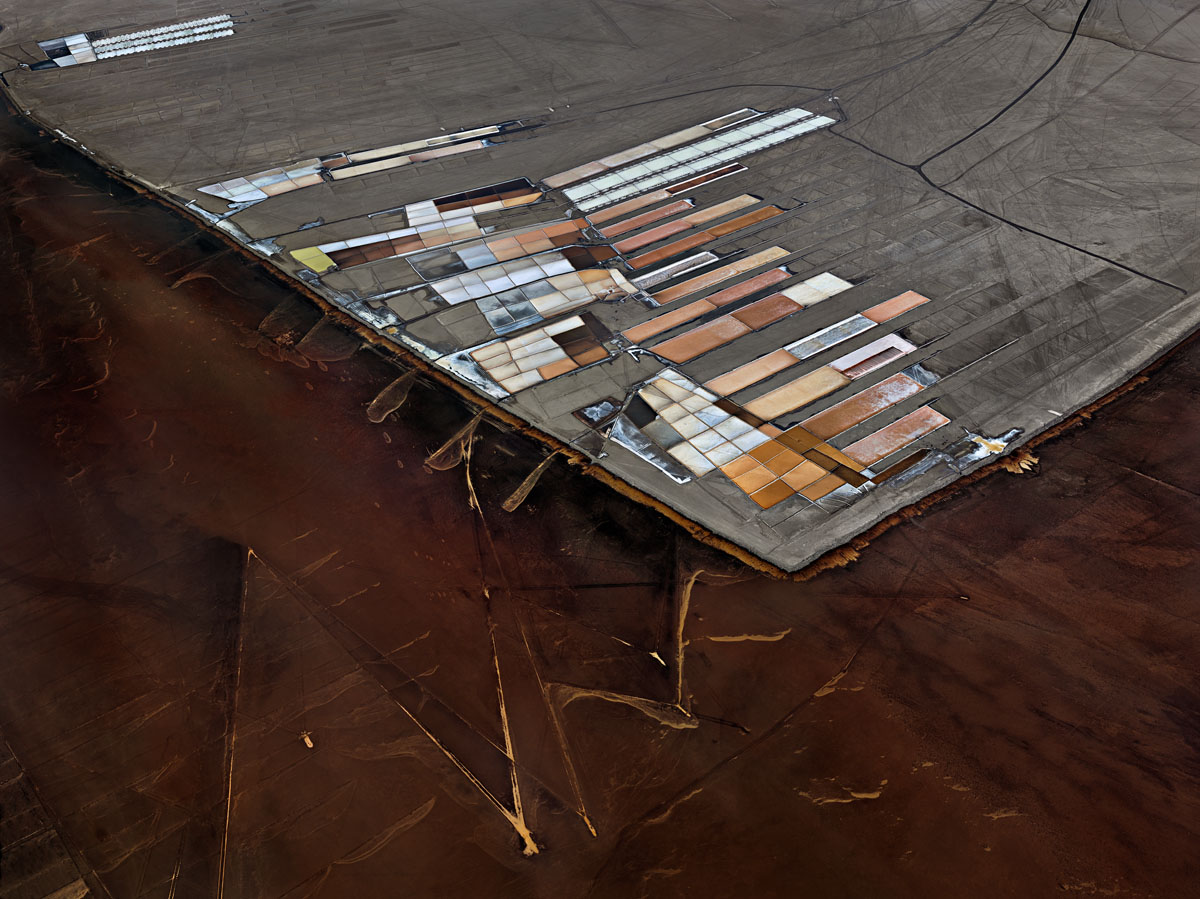

Salt Pans

For this series Burtynsky traveled to Gujarat, India, to photograph the Little Rann of Kutch, a region that is home to more than 100,000 salt workers extracting around one million tons of salt from the floodwaters of the Arabian Sea each year. Salt has been their main industry for the last four hundred years. Receding groundwater levels and declining market values will in time make this way of life obsolete and will cause the salt pans to disappear.

From an aerial vantage point approximately 500 - 800 feet above the ground, Burtynsky photographed this unusual landscape of multi-coloured interlocking rectangles, spanning across the delta. In recent years, Burtynsky’s photographs have become increasingly abstract as a result of his topographical perspective and fascination with finding similarities in the industrialized landscape to painting. Salt Pans continues in this direction with Burtynsky exploring the subtle modulations of tone and compositional balance of the pans, and the calligraphic tracks from vehicles referencing scale and human activity. Burtynsky’s images encapsulate the delicate balance between natural and human processes – the presence of salt in the earth’s composition and our need to harness it.

"The images in this book are not about the battles being fought on the ground. Rather, they examine this ancient method of providing one of the most basic elements of our diet; as primitive industry and as abstract two-dimensional human marks upon the landscape."

— Edward Burtynsky

Water

ARTIST STATEMENT

“While trying to accommodate the growing needs of an expanding, and very thirsty civilization, we are reshaping the Earth in colossal ways. In this new and powerful role over the planet, we are also capable of engineering our own demise. We have to learn to think more long-term about the consequences of what we are doing, while we are doing it. My hope is that these pictures will stimulate a process of thinking about something essential to our survival; something we often take for granted—until it’s gone.”

"I wanted to understand water: what it is, and what it leaves behind when we're gone. I wanted to understand our use and misuse of it. I wanted to trace the evidence of global thirst and threatened sources. Water is part of a pattern I've watched unfold throughout my career. I document landscapes that, whether you think of them as beautiful or monstrous, or as some strange combination of the two, are clearly not vistas of an inexhaustible, sustainable world."

(Walrus, October 2013)

"The project takes us over gouged landscapes, fractal patterned delta regions, ominously coloured biomorphic shapes, rigid and rectilinear stepwells, massive circular pivot irrigation plots, aquaculture and social, cultural and ritual gatherings. Water is intermittently introduced as a victim, a partner, a protagonist, a lure, a source, an end, a threat and a pleasure. Water is also often completely absent from the pictures. Burtynsky instead focusses on the visual and physical effects of the lack of water, giving its absence an even more powerful presence." - Russell Lord - Curator of Photographs - NOMA

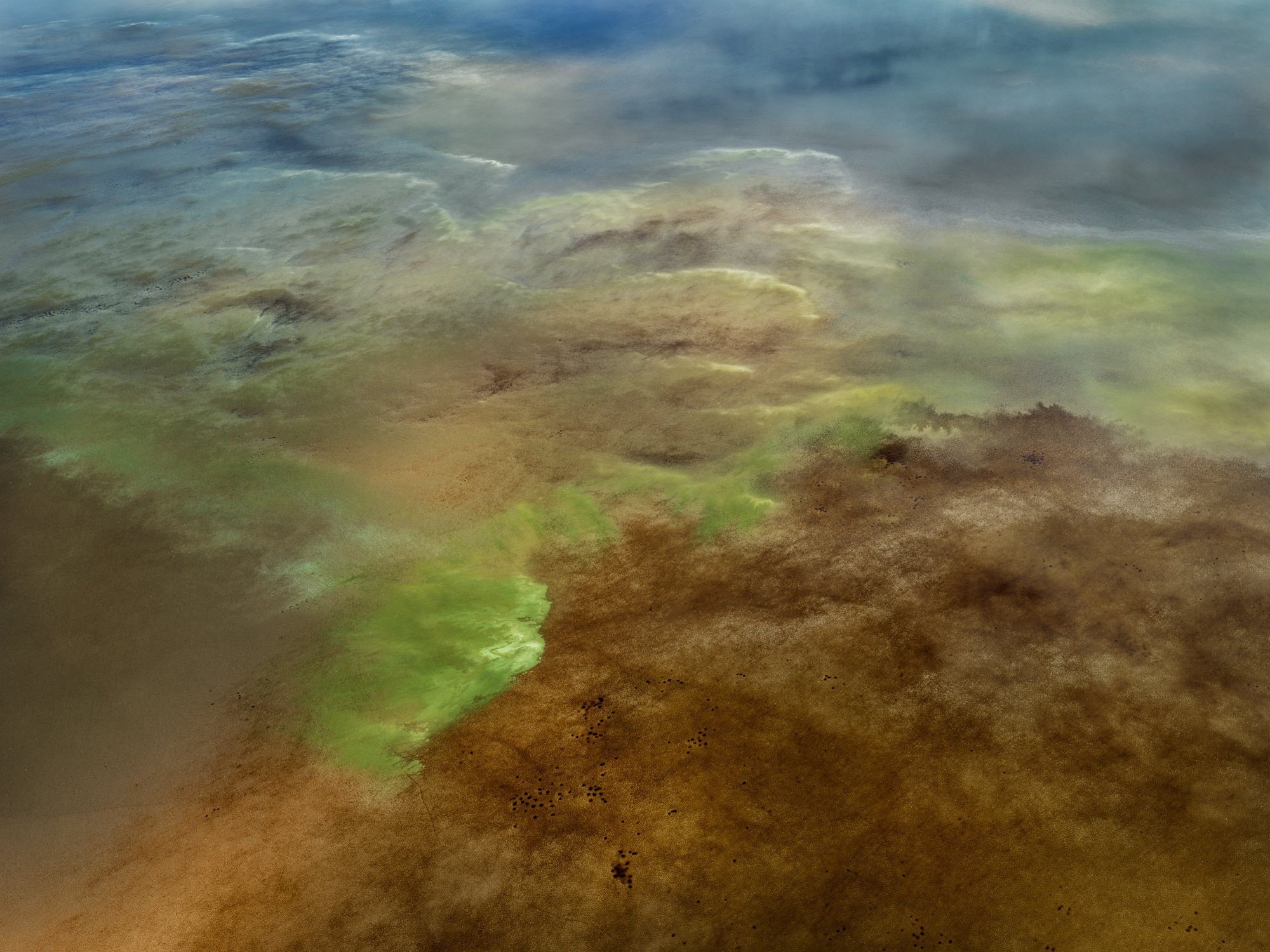

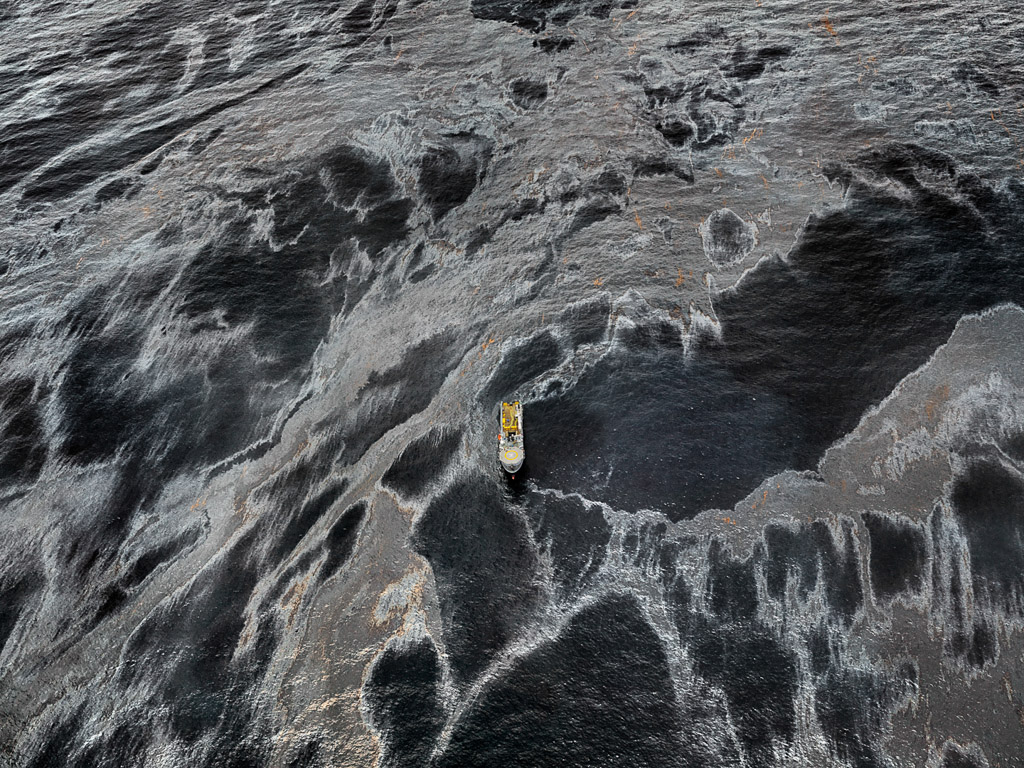

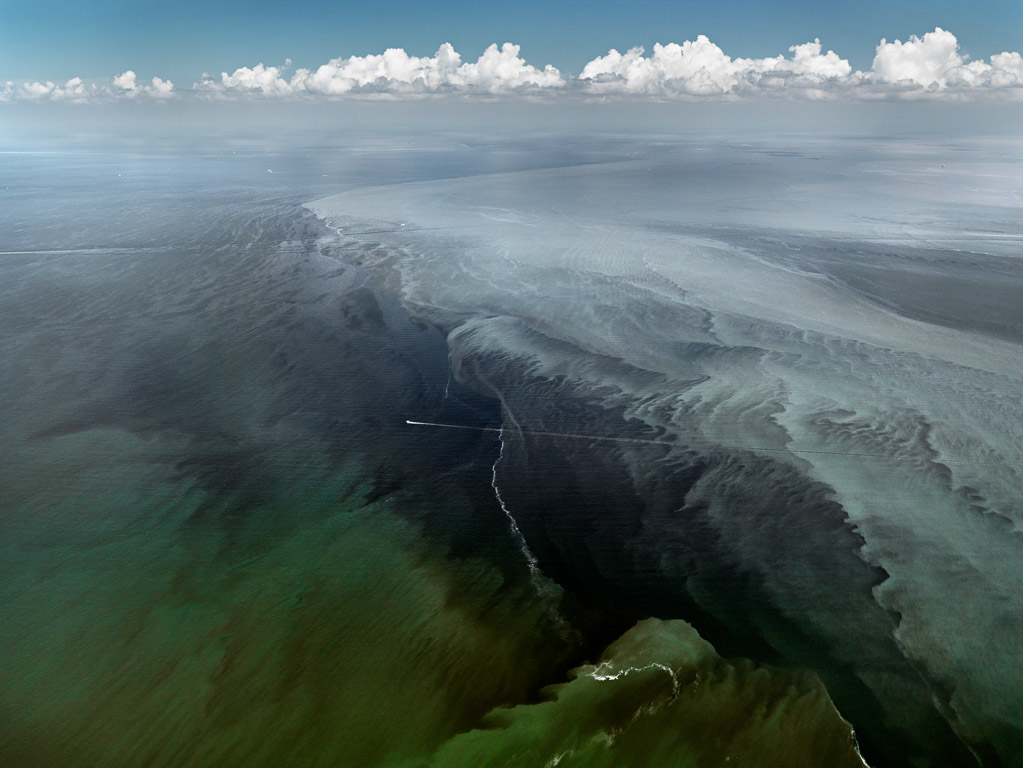

GULF of MEXICO:

When BP’s Deepwater Horizon well began pouring millions of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico in May 2010, Edward Burtynsky traveled to the site to capture the event. Though characteristically spectacular and expressly an evolution of the photographer’s more recent aerial shooting method, the images present something of a departure for Burtynsky, who has said of his work “I understand that it has an editorial aspect to it, but nothing I photograph is typically a news event. I’m not so much into chasing disasters as I am into looking at big industrial incursions into the landscape or in this case, the seascape.”

This Oil Spill imagery, while expressing the familiar grand scale of Burtynsky’s oeuvre, also depicts an event that is newsworthy—even as it is alchemized into art. As a result, there is a notable degree to which these pictures “inform the typically omniscient viewpoint with an charge of topicality.”

DISTRESSED:

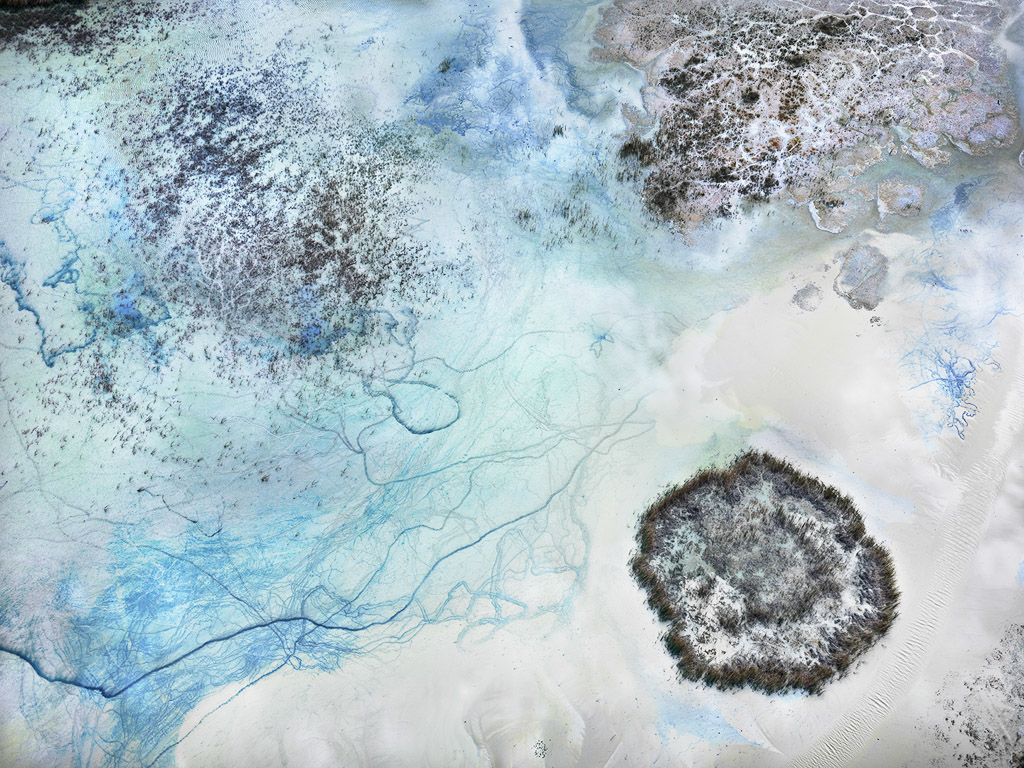

Landscapes where water is scarce or forever compromised such as the Salton Sea, the Colorado River Delta, that has not seen a drop of water from that river in over forty years, and is now a desert; or Owens Lake, that saw its water diverted to Los Angeles in 1913 and is now a dry, toxic lakebed.

CONTROL:

This chapter examines large-scale incursions imposed upon the earth to harness and divert the power of water; from the ancient Stepwells of India, to the modern canals that feed precious water to millions in California, and gigantic hydroelectric dam projects of China.

AGRICULTURE:

Agriculture represents - by far - the largest human activity upon the planet. Approximately seventy percent of all fresh water under our control is dedicated to this activity.

AQUACULTURE:

Aquaculture provides a glimpse into this quickly growing and increasingly important food source. Aquaculture looks as those places where land and sea is been shaped to serve the purposes of growing and harvesting water-based crops such as salt, fish, shrimp, seaweed and rice.

WATERFRONT:

Waterfront looks at the way we shape land to create manufactured waterfront properties, and speaks about the human need and desire to be near water—even if it is artificial. Burtynsky also takes us to India, to witness the largest pilgrimage on the planet with 35 million people arriving to bathe in the Ganges to release them of their sins—an ancient spiritual belief in the cleansing power and sacredness of water.

SOURCE:

Source comes from Burtynsky’s journey to British Columbia and Iceland, places where a critical stage in the hydrological cycle takes place: the mountains, containing glaciers and snow. They are the first landscapes in over thirty years Burtynsky took focussing specifically on pristine wilderness, instead of the imposition of human systems upon it.

Oil

ARTIST STATEMENT

"When I first started photographing industry it was out of a sense of awe at what we as a species were up to. Our achievements became a source of infinite possibilities. But time goes on, and that flush of wonder began to turn. The car that I drove cross-country began to represent not only freedom, but also something much more conflicted. I began to think about oil itself: as both the source of energy that makes everything possible, and as a source of dread, for its ongoing endangerment of our habitat.

I wanted to represent one of the most significant features of this century: the automobile. The automobile is the main basis for our modern industrial world, giving us a certain freedom and changing our world dramatically. The automobile was made possible because of the invention of the internal combustion engine and its utilization of both oil and gasoline. The raw material and the refining process contained both the idea and an interesting visual component for me."

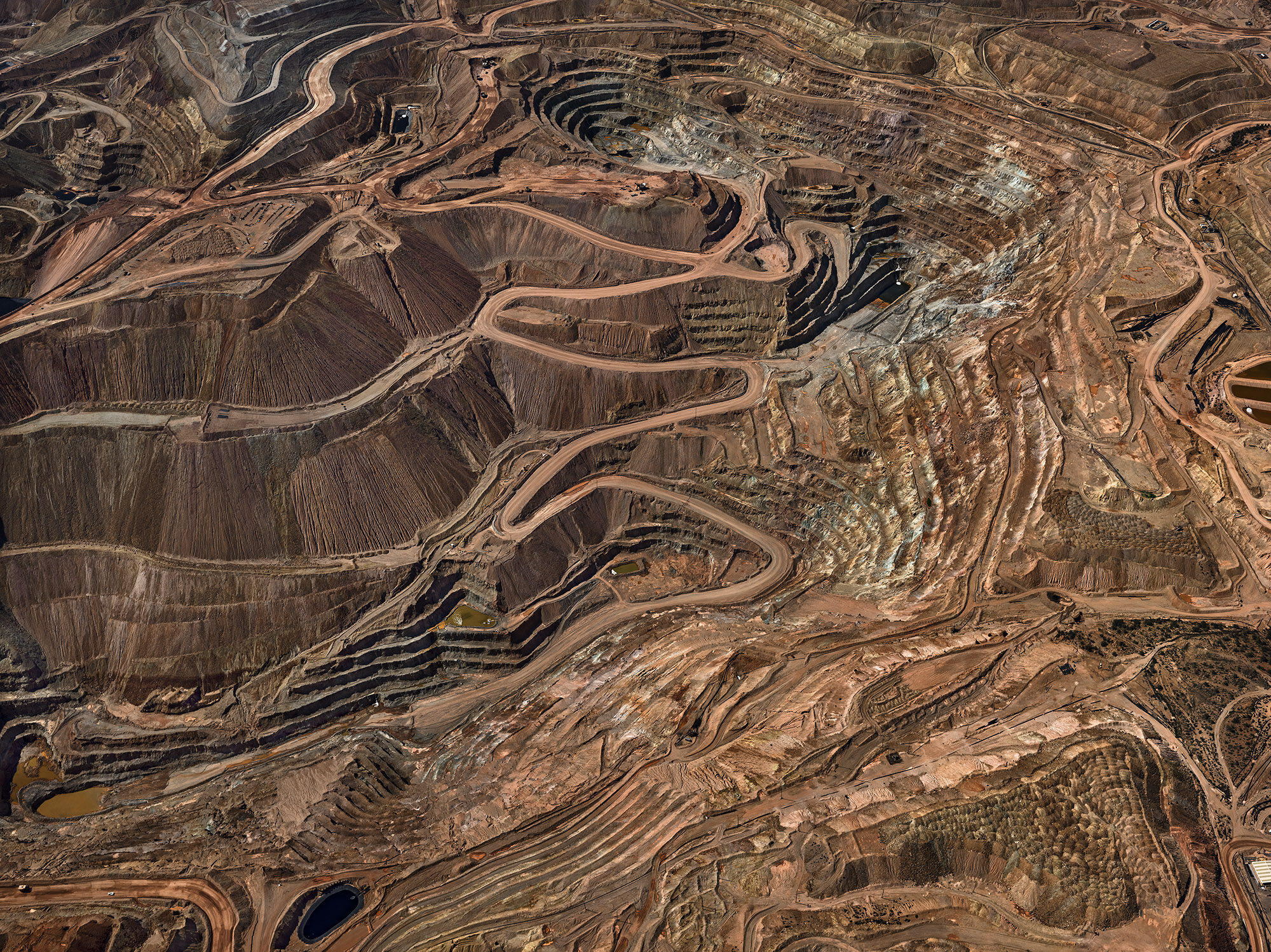

Mines

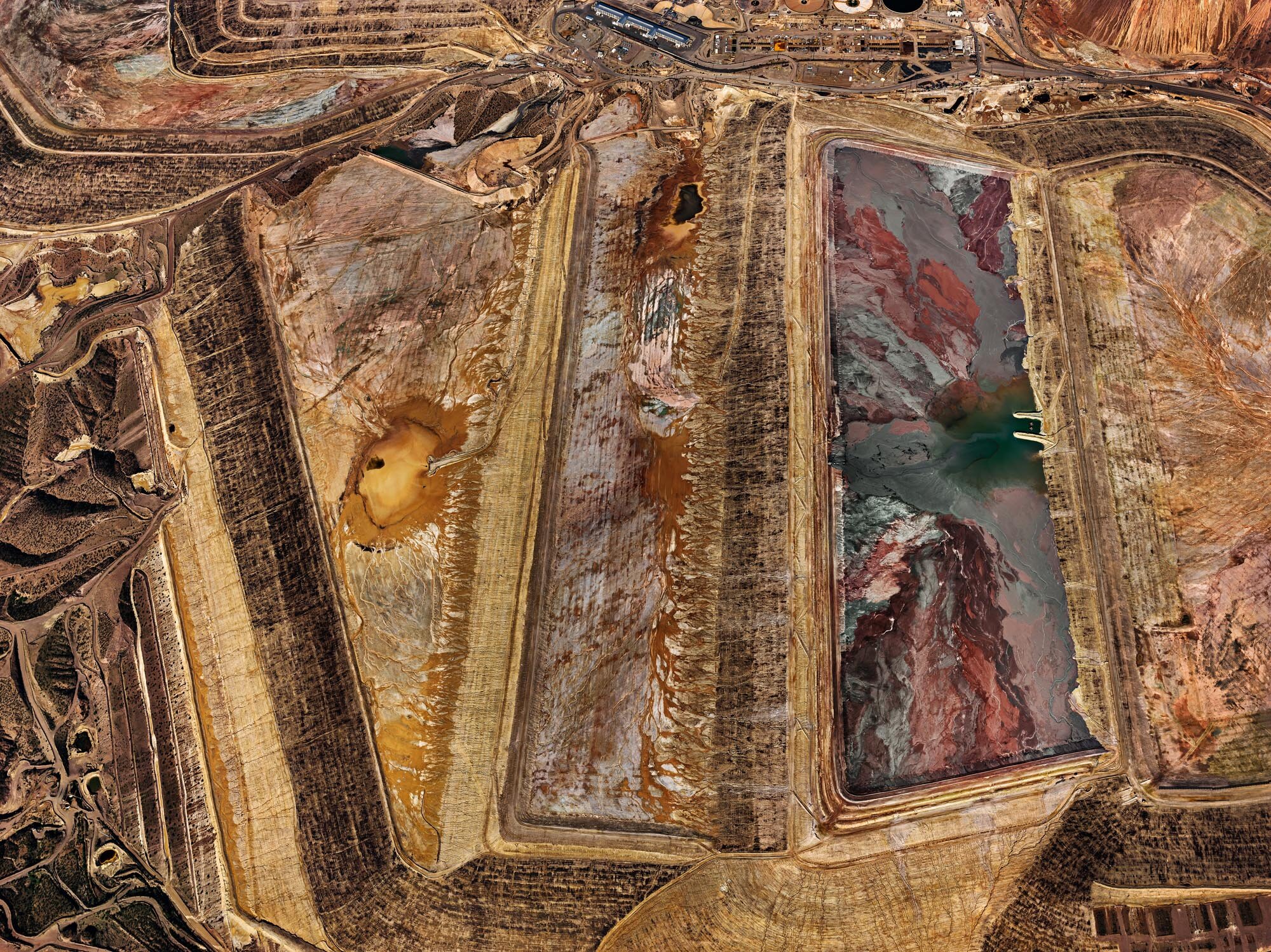

MINES:

In Burtynsky's images, it is the insatiable human appetite for the world's raw materials that is of primary interest. The tools of manufacturing are sometimes included, but they often function simply as a measure of the immense scale of the scene before us.

AUSTRALIA:

What is at first glance merely a scarred landscape becomes poetic evidence of resources spent, nature transformed as well as realized―or failed―hopes and dreams. The aerial images of the Silver Lake Operations at Lake Lefroy and of the pits and tailings at Kalgoorlie, along with the Dampier Salt Ponds are among the most handsome that Burtynsky has ever made. They combine a kind of mapping with a keenly felt experience of all the hard rock grit, dust and labour transforming these arid lands.

Quarries

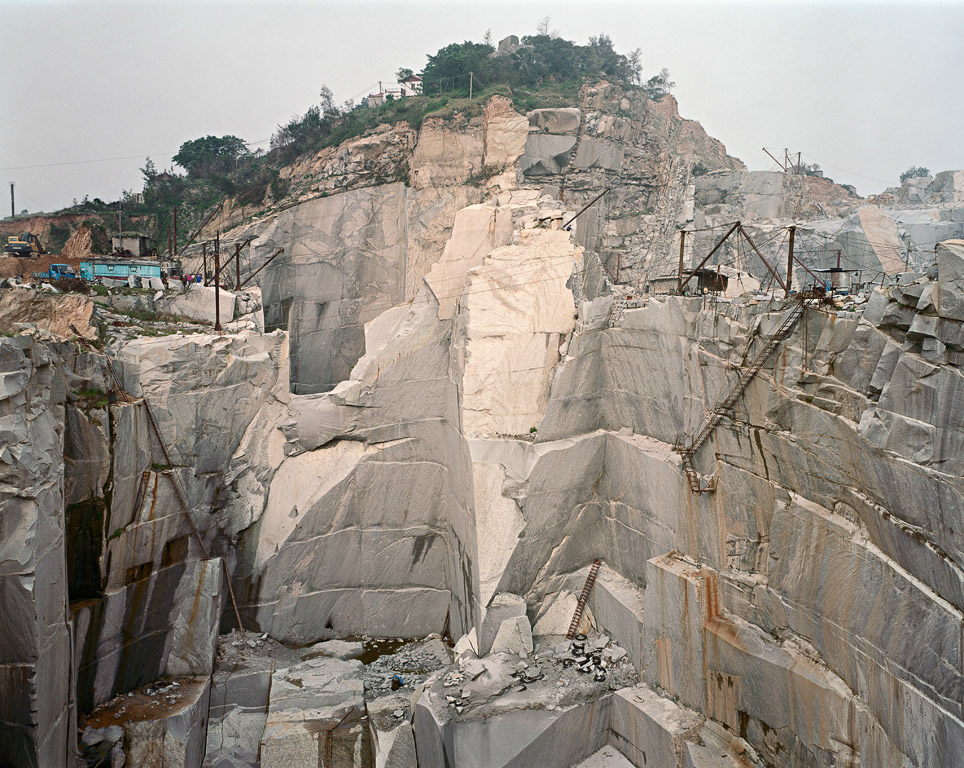

ARTIST STATEMENT

“The concept of the landscape as architecture has become, for me, an act of imagination. I remember looking at buildings made of stone, and thinking, there has to be an interesting landscape somewhere out there because these stones had to have been taken out of the quarry one block at a time. I had never seen a dimensional quarry, but I envisioned an inverted cubed architecture on the side of a hill. I went in search of it, and when I had it on my ground glass, I knew that I had arrived. I had found an organic architecture created by our pursuit of raw materials. Open-pit mines, funneling down, were to me like inverted pyramids. Photographing quarries was a deliberate act of going out to try to find something in the world that would match the kinds of forms in my imagination.”

“I was excited by the striking patinas on the walls of the abandoned quarries. The surface of the rock-face would simultaneously reveal the process of its own creation, as well as display the techniques of the quarrymen. I likened the tenacious trees and pools of water to nature's sentinels awaiting the eventual retreat of man and machine - to begin the slow process of reclamation.”

“Often my approach, the compression of space through light and optics, also yields an ambiguity of scale. I think that people are always trying to put a human scale on things. We need to put our human perspective into these images, and our presence is dwarfed by the spaces we’ve created. It's an interesting metaphor for how technology seems larger than life, larger than our own lives.”

VERMONT:

Edward Burtynsky got to Barre for the first time in 1991 as a result of a photographic quest for quarries in Northern Ontario. When he expressed his disappointment with the small scale of operations in Temagami, a quarryman there described a series of spectacular quarries he’d seen in Vermont. He packed his gear and began the long drive southeast to Barre. It was a trip that launched his career.

For the artist, it suggested inverted architecture: an idea about quarries that he had long dreamed of, but in the eyes of the quarryman it was an evolutionary history of extraction technology. In all, Edward Burtynsky made a half dozen Vermont trips to photograph what are thought to be the deepest quarries in the world.

CARRARA:

Like many of us, Burtynsky went to Carrara dreaming of Michelangelo. But after a long flight and an even longer mountain drive he found the road to the master’s favourite quarry chained off a dozen kilometers from the source. His view of that historic marble mountain from across the adjacent valley records the closest he ever got. Yet frustrated plans can yield unexpected opportunities. A nearby quarry suggested as an alternative proved to be a picture-maker’s windfall. The creamy, flawless marble made a perfect white ground for the machines, cables and tools of the quarryman’s trade. In the diptych Carrara Marble Quarries # 24 & 25, the chainsaw-like block cutters slowly make their way along short track sections on the quarry floor. It’s as if they’re cutting cake. Today there are over one hundred active quarries around Carrara. They employ a thousand workers who extract a million tons of marble each year.

MAKRANA:

The marble quarries of Makrana have supplied stone for some of the most storied and beautiful structures in all of human history―the Jain temples of Mount Abu and Ranakur and that shimmering monument to lost love, Agra’s Taj Mahal. However, for many Indians the Makrana quarries are the Pits of Death. At least half a dozen workers die in the quarries every month and there have been more than 500 serious accidents in the past half decade. Additionally, there is an enormous and poorly documented host of occupational illnesses and injuries—silicosis, deafness and loss of limbs. In 2005 alone, more than fifty local mines collapsed. This beauty has an enormous capital cost.

The requisite dynamite blasts are regularly set off with no advance warning to workers in the pits. A worker here must be fearless. There is always an adjacent mosque for prayers by the Muslim workforce. When Burtynsky was photographing the region’s largest quarry, an enormous block being hoisted by cable slipped free and crashed down the bedding slope, firing rock chips at the photographer and his crew. For the quarry owners, workers who survive to age thirty-five are old and obsolete.

XIAMEN:

Since Deng Xiaoping began opening China’s economy to the world in 1978, economic growth in coastal provinces like Fujian has been phenomenal. The high-grade granites near Xiamen have led to the development of more than a hundred local quarries and thousands of stone product workshops employing nearly a million people. The skilled stone carvers seen working in image China Quarries #8 will make you a life-size likeness of Michelangelo’s David in granite for under a thousand dollars. Send them a photograph of yourself and they’ll do one of you for the same price.

The story of this trade in China is very similar to that of its main rival, India. Their vigorous assault on the land reminds us of our own experience in the West more than a century before.

IBERIA:

The quarries of southeastern Portugal are often extremely deep. The operation in Iberia Quarries #9 has reached a depth of more than 450 feet. These pits, with their precipitous walls and profound depths, dictated extreme solutions to the photographer’s fundamental problem of where to stand. The photograph of the Cochico company’s quarry at Pardais (Iberia Quarries #8) was made using one of the orange-painted elevator platforms cantilevered from the lower right wall of the pit. Here, nearly a quarter century after his initial encounter with the quartz mine photograph at Canada’s National Gallery, Burtynsky had finally found a site that allowed him to make homage to the inspiration provided by August Sander. For Burtynsky, these Portuguese quarries represented the culmination and conclusion of a fifteen-year search for his dream image of an architecture turned inside out and upside down. Turn the image Iberia Quarries #3 upside down and there it finally is – the inverted ziggurat that he had so long imagined. His quarry work was complete.

China

ARTIST STATEMENT

“…. mass consumerism… and the resulting degradation of our environment intrinsic to the process of making things to keep us happy and fulfilled frightens me. I no longer see my world as delineated by countries, with borders, or language, but as 7 billion humans living off a single, finite planet.”

COAL & STEEL:

Bao Steel is the sixth largest steel producer in the world. The company employs 15,600 people. Almost all of Bao Steel’s iron ore is imported, being sourced in Australia, Brazil, South Africa and India.

MANUFACTURING:

In the province of Guangdong, one can drive for hours along numerous highways that reveal a virtually unbroken landscape of factories and workers’ dormitories. These new ‘manufacturing landscapes’ in the southern and eastern parts of China produce more and more of the world’s goods and have become the habitat for a diverse group of companies and millions of busy workers.

OLD INDUSTRY:

State-owned enterprises are rapidly being demolished and rebuilt at industrial parks outside the city, along with many other new factories. Property once used by these immense old factories is now being designated as residential and commercial, spurring real estate frenzy in Shenyang. Inexpensive labor from the countryside, important as it is to China’s growth as a trading nation, is one major facet of its success. Just as important is a rising industrial production capability. China now plays a central role in the global supply chain for the world’s multinational corporations.

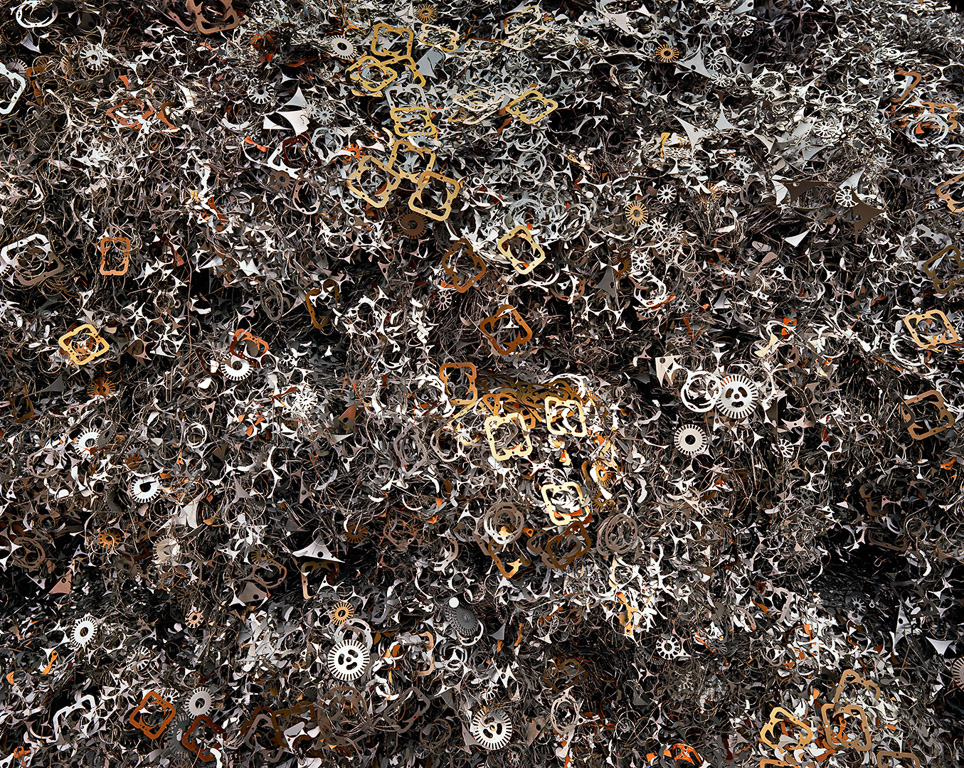

RECYCLING:

E-waste is hazardous and its processing is a high-risk endeavor even in state-of-the-art facilities. In China, e-waste recycling is, for the most part, not yet a refined industry. Once the scrap arrives at its destination, workers use their hands and primitive tools to pick apart the junked computers and salvage precious components. In the process they expose themselves and their environment to toxic elements such as lead, mercury and cadmium.

SHIPYARDS:

With over 12,000 workers using 500,000 tons of steel, Qili port shipyards build 232 to 250 ships per year. According to the Chinese Commission for Science, Technology and and National Defense, by 2015 China is expected to become the world’s largest shipbuilder, with annual output reaching 24 million deadweight tons, or 35 per cent of the world’s total.

URBAN RENEWAL:

The images in the China series communicate the enormity of the transition that is taking place there as the country moves increasingly towards a large-scale urbanization and more workers relocate for employment in the manufacturing industries. Not only are new cities emerging but immense urban renewal efforts are also underway.

THREE GORGES DAM:

Building mega dams in the 21st century has gathered much global criticism and is central to a growing debate. To make room for the Three Gorges Dam, approximately 1.13 million people must be relocated and their livelihoods challenged. It is the largest peacetime evacuation in history. Fertile agricultural lands and important cultural/historic sites will be found submerged under a vast reservoir.

Shipbreaking

Burtynsky's Shipbreaking photographs, like all his works, appear to us as images of the end of time. The abandoned mines and quarries, the piles of discarded tires, the endless fields of oil derricks, and the huge monoliths of retired tankers show how our attempts at industrial "progress" often leave a residue of destruction. Nevertheless there is something uncannily beautiful and breathtaking in the very expansiveness of these images―it is as if the vastness of their perspective somehow opens onto the longer view of things. For Burtynsky, nature itself, over time, can reclaim even the most ambitious of human incursions into the land. As long as human needs and desires change, so too will the landscape.

“The original idea for the shipbreaking started a long time ago. About four years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill I heard a radio program where theywere talking about the danger of single-hulled ships. The insurance companies were refusing to cover them after 2004, which would force all these ships to be decommissioned. Only double-hulled ships would be allowed on the open sea to prevent that kind of catastrophe from happening again.

What went off in my mind was, wouldn’t it be interesting to see where these massive vessels will be taken apart. It would be a study of humanity and the skill it takes to dismantle these things. I looked upon the shipbreaking as the ultimate in recycling, in this case of the largest vessels ever made. It turned out that most of the dismantling was happening in India and Bangladesh so that's where I went.”

Urban Mines

We've never stopped taking things from nature. Even the act of taking from the earth is natural since we are not outside of nature. What is different today is the scale. Current society is searching for a way to come to terms with that taking from the earth. Recycling is one way we can put a stop to a certain amount of damage to the earth. This material comes from and collects around urban centres in large recycling yards. These yards are like secondary mines.

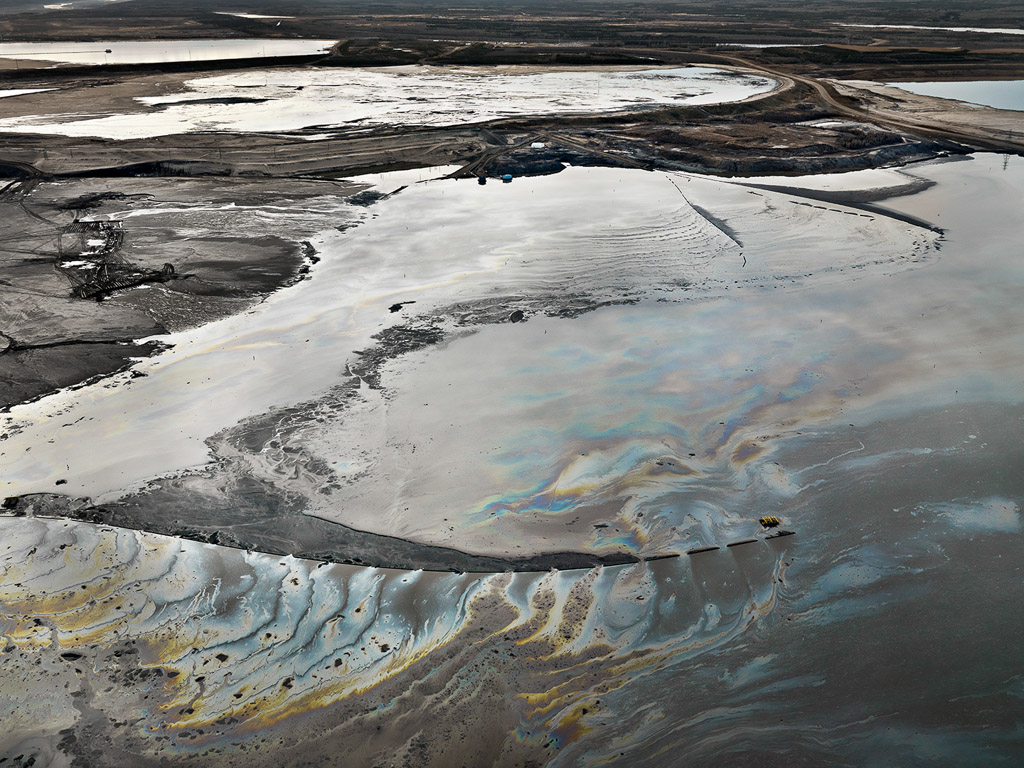

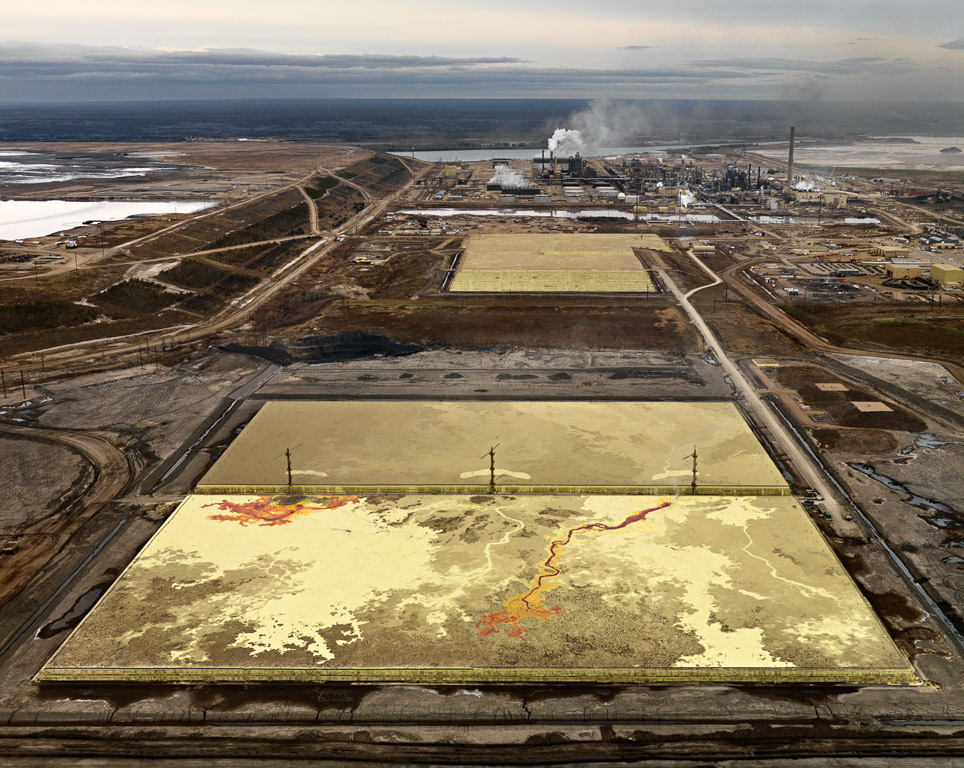

Tailings

Burtynsky's skill as a photographic colourist is evident in most of his work, but perhaps most strikingly in a group of photographs of nickel tailings near Sudbury, Ontario. Juxtaposing pulsating orange against a glossy black background, he extracts spectacular images from a landscape that many might consider unphotogenic. The startling colours are those we see when lava flows from an erupting volcano, which is perhaps why we immediately associate this image with natural disaster. In actual fact, the intense reds and oranges are caused by the oxidation of the iron that is left behind in the process of separating nickel and other metals from the ore.

Early Landscapes

Burtynsky’s evolving compositional strategies were also informed by a marked desire to explore how the visual properties of modernist painting might be made relevant to colour landscape photography. Foremost in his mind was the Abstract Expressionist treatment of pictorial space as a dense, compressed field evenly spread across the entire surface of a large composition. Emphasizing these pictorial concerns within the landscape tradition was for him another way to contribute to the field and to assert the relevance of painting to his photographic practice.

Homesteads

From the beginning of his career, Burtynsky was attuned to the delicate balance that exists between humans and the environment. We can see this clearly in a series of photographs he called Homesteads. The title evokes images of the self-reliant pioneers of the nineteenth century, a theme that presents itself in images such as Homesteads #30. In the Homesteads series, the precise geographic location, whether in British Columbia, Alberta, Montana, or upstate New York, is not really significant, since the primary elements remain the same: the small homes and outbuildings dotting the nearly empty land. The central meaning of these pictures is the rudimentary interaction between people and the land.

Railcuts

Even in his choice of a title for this series, Burtynsky informs us that his photographs do not share an aesthetic agenda with earlier images of the railway. The title Railcuts evokes a sense of direct physical contact with the land. Blasted rock-face fills most of the frames in these images, and the tightly cropped views of the railway line seen head-on are strangely airless and even claustrophobic. Compared with the deep perspective used in works by nineteenth-century photographers who worked for the Canadian Pacific Railway, Burtynsky's viewpoint is close and confrontational. — Lori Pauli